Radiation and Health Effects

- Radiation is a well-understood process, with natural sources accounting for most of the radiation we all receive each year.

- Contrary to public perception, nuclear power accidents have caused very few fatalities and the use of nuclear energy does not expose members of the public to significant radiation levels.

- The socio-economic and psychological impacts of radiation fears in the aftermath of nuclear accidents have caused considerable harm amongst exposed and non-exposed populations.

- Current radiation protection standards assume that any dose of radiation, no matter how small, involves a risk to human health.

Radiation plays a key role in modern life, be it the use of nuclear medicine, space exploration or electricity generation. Radiation constantly surrounds us as a result of naturally occurring radioactive elements in, for example, the soil, the air and the human body. As a result of many decades of research, the health impacts of radiation are very well-understood. In a 2016 report the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) noted:

“We know more about the sources and effects of exposure to [ionizing] radiation than to almost any other hazardous agent, and the scientific community is constantly updating and analysing its knowledge... The sources of radiation causing the greatest exposure of the general public are not necessarily those that attract the most attention."

At its most fundamental level, radioactivity is a question of energy, and the desire for unstable elements to become stable. By releasing radiation, elements go from one energy state to another which, eventually, will result in an element no longer being radioactive. There is a distinction to be drawn between radioactivity on the one hand, and radioactive elements on the other. Radioactivity is the process of releasing energy, either by particles (α, β) or high-energy photons (γ, X-ray).

A radioactive element is an element which can decay due to the aforementioned energy imbalance, a process which might take less than a second, or billions of years. As these unstable elements, known as radionuclides, decay, they often become a different element as well as release energy, which is measured in electron volts (eV). Many radionuclides exist in nature, but many are also created in different nuclear reactions, such as in stars or nuclear reactorsa.

Radiation particularly associated with nuclear medicine and the use of nuclear energy, along with X-rays, is 'ionizing' radiation, which means that the radiation has sufficient energy to interact with matter, especially the human body, and produce ions, i.e. it can eject an electron from an atom. This interaction between ionizing radiation and living tissue can cause damage.

X-rays from a high-voltage discharge were discovered in 1895, and radioactivity from the decay of particular isotopes was discovered in 1896. Many scientists then undertook study of these, and especially their medical applications. This led to the identification of different kinds of radiation from the decay of atomic nuclei, and understanding of the nature of the atom. Neutrons were identified in 1932, and in 1939 atomic fission was discovered by irradiating uranium with neutrons. This led on to harnessing the energy released by fission.

Types of radiation

Nuclear radiation arises from hundreds of different kinds of unstable atoms. The energy of each kind of radiation is measured in electron volts (eV). The principal kinds of ionizing radiation are:

Alpha particles

Alpha (α) particles consist of two protons and two neutrons, and are positively charged. They are often very energetic, but because of their large size they cannot travel very far before they lose this energy. They are stopped by a sheet of paper or skin and are only a potential health concern if they are ingested or inhaled.

The alpha particles’ large size, relatively speaking, and high energy are key to understanding their health impacts. When inside the human body, alpha particles can cause damage to the cells and to DNA as their size makes it more likely that it will interact with matter. If the dose is too high for repairs to be made satisfactorily, there is a potential increase in the risk of getting cancer later in life.

Examples of alpha emitters: uranium-238, radon-222, plutonium-239.

Beta particles

Beta (β) particles are electrons with high energy. Beta particles are 1/8000th the size of an alpha particle, which means that it can travel further before being stopped, but a sheet of aluminium foil is enough to stop beta particles. Equally, its small size results in its ionising power being considerably smaller than that of alpha particles (by about 10 times). This stems from the fact that the human body (and all matter more generally) is mainly made up of ‘empty’ space. The smaller the particle, the lower the risk of it colliding with parts of the atom which, in turn, lowers the risk of damage.

Examples of beta emitters: caesium-137, strontium-90, hydrogen-3 (tritium).

Gamma rays

These are high-energy electromagnetic waves much the same as X-rays. They are emitted in many radioactive decays and may be very penetrating, so require more substantial shielding. The energy of gamma rays depends on the particular source. Gamma rays are the main hazard to people dealing with sealed radioactive materials used, for example, in industrial gauges and radiotherapy machines. Radiation dose badges are worn by workers in exposed situations to monitor exposure. All of us receive about 0.5-1 mSv per year of gamma radiation from rocks, and in some places, much more. Gamma activity in a substance (e.g. rock) can be measured with a scintillometer or Geiger counter.

Other types of radiation

X-rays are also electromagnetic waves and ionizing, virtually identical to gamma rays, but not nuclear in origin. They are produced in a vacuum tube where an electron beam from a cathode is fired at target material comprising an anode, so are produced on demand rather than by inexorable physical processes. (However the effect of this radiation does not depend on its origin but on its energy. X-rays are produced with a wide range of energy levels depending on their application.)

Cosmic radiation consists of very energetic particles, mostly high-energy protons, which bombard the Earth from outer space. They comprise about one-tenth of natural background exposure at sea level, and more at high altitudes.

Neutrons are uncharged particles mostly released by nuclear fission (the splitting of atoms in a nuclear reactor), and hence are seldom encountered outside the core of a nuclear reactor.* Thus they are not normally a problem outside nuclear plants. Fast neutrons can be very destructive to human tissue. Neutrons are the only type of radiation which can make other, non-radioactive materials, become radioactive.

* Large nuclei can fission spontaneously, since the so-called strong nuclear force holding each nucleus together is not overwhelmingly stronger than the repulsive force of charged protons.

Units of radiation and radioactivity

In order to quantify how much radiation we are exposed to in our daily lives and to assess potential health impacts as a result, it is necessary to establish a unit of measurement. The basic unit of radiation dose absorbed in tissue is the gray (Gy), where one gray represents the deposition of one joule of energy per kilogram of tissue.

However, since neutrons and alpha particles cause more damage per gray than gamma or beta radiation, another unit, the sievert (Sv) is used in setting radiological protection standards. This weighted unit of measurement takes into account biological effects of different types of radiation and indicates the equivalent dose. One gray of beta or gamma radiation has one sievert of biological effect, one gray of alpha particles has 20 Sv effect and one gray of neutrons is equivalent to around 10 Sv (depending on their energy). Since the sievert is a relatively large value, dose to humans is normally measured in millisieverts (mSv), one-thousandth of a sievert.

Note that Sv and Gy measurements are accumulated over time, whereas damage (or effect) depends on the actual dose rate, e.g. mSv per day or year, Gy per day in radiotherapy.

The becquerel (Bq) is a unit or measure of actual radioactivity in material (as distinct from the radiation it emits, or the human dose from that), with reference to the number of nuclear disintegrations per second (1 Bq = 1 disintegration/sec). Quantities of radioactive material are commonly estimated by measuring the amount of intrinsic radioactivity in becquerels – one Bq of radioactive material is that amount which has an average of one disintegration per second, i.e. an activity of 1 Bq. This may be spread through a very large mass.

Radioactivity of some natural and other materials

| 1 banana | 15 Bq |

| 1 kg of brazil nuts | 400 Bq |

| 1 kg of coffee | 1000 Bq |

| 1 kg of granite | 1000 Bq |

| 1 kg of coal ash | 2000 Bq |

| 1 adult human (65 Bq/kg) | 4500 Bq |

| 1 kg of superphosphate fertilizer | 5000 Bq |

| 1 household smoke detector (with americium) | 30 000 Bq |

| 1 kg uranium ore (Australian, 0.3%) | 500 000 Bq |

| 1 kg low level radioactive waste | 1 million Bq |

| 1 kg uranium ore (Canadian, 15%) | 25 million Bq |

| Radioisotope for medical diagnosis | 70 million Bq |

| 1 luminous Exit sign (1970s) | 1,000,000 million Bq |

| 1 kg 50-year-old vitrified high-level waste | 10,000,000 million Bq |

| Radioisotope source for radiotherapy | 100,000,000 million Bq |

N.B. Though the intrinsic radioactivity is the same, the radiation dose received by someone handling a kilogram of high-grade uranium ore will be much greater than for the same exposure to a kilogram of separated uranium, since the ore contains a number of short-lived decay products, while the uranium has a very long half-life.

Older units of radiation measurement continue in use in some literature:

Rads (100 rads = 1 gray)

Rem (100 rem = 1 sievert)

Curies (27 picocuries or 2.7 x 10-11 curies = 1 bequerel)

One curie was originally the activity of one gram of radium-226, and represents 3.7 x 1010 disintegrations per second (Bq).

The working level month (WLM) has been used as a measure of dose for exposure to radon and in particular, radon decay productsb.

Since there is radioactivity in many foodstuffs, there has been a whimsical suggestion that the Banana Equivalent Dose from eating one banana be adopted for popular reference. This is about 0.0001 mSv.

Routine sources of radiation

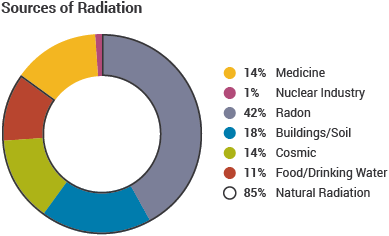

Radiation can arise from human activities or from natural sources. Most radiation exposure is from natural sources. These include: radioactivity in rocks and soil of the Earth's crust; radon, a radioactive gas given out by many volcanic rocks and uranium ore; and cosmic radiation. The human environment has always been radioactive and accounts for up to 85% of the annual human radiation dose.

Helpful depictions of routine sources of radiation can be found on the information is beautiful and xkcd websites.

Radiation arising from human activities typically accounts for up to 20% of the public's exposure every year as global average. In the USA by 2006 it averaged about half of the total. This radiation is no different from natural radiation except that it can be controlled. X-rays and other medical procedures account for most exposure from this quarter. Less than 1% of exposure is due to the fallout from past testing of nuclear weapons or the generation of electricity in nuclear, as well as coal and geothermal, power plants.

Backscatter X-ray scanners being introduced for airport security will gives exposure of up to 5 microsieverts (μSv), compared with 5 μSv on a short flight and 30 μSv on a long intercontinental flight across the equator, or more at higher latitudes – by a factor of 2 or 3. Aircrew can receive up to about 5 mSv/yr from their hours in the air, while frequent flyers can score a similar incrementc. On average, nuclear power workers receive a lower annual radiation dose than flight crew, and frequent flyers in 250 hours would receive 1 mSv.

The maximum annual dose allowed for radiation workers is 20 mSv/yr, though in practice, doses are usually kept well below this level. In comparison, the average dose received by the public from nuclear power is 0.0002 mSv/yr, which is of the order of 10,000 times smaller than the total yearly dose received by the public from background radiation.

Natural background radiation, radon

Naturally occurring background radiation is the main source of exposure for most people, and provides some perspective on radiation exposure from nuclear energy. Much of it comes from primordial radionuclides in the Earth’s crust, and materials from it. Potasssium-40, uranium-238 and thorium-232 with their decay products are the main source.

The average dose received by all of us from background radiation is around 2.4 mSv/yr, which can vary depending on the geology and altitude where people live – ranging between 1 and 10 mSv/yr, but can be more than 50 mSv/yr. The highest known level of background radiation affecting a substantial population is in Kerala and Madras states in India where some 140,000 people receive doses which average over 15 millisievert per year from gamma radiation, in addition to a similar dose from radon. Comparable levels occur in Brazil and Sudan, with average exposures up to about 40 mSv/yr to many people. (The highest level of natural background radiation recorded is on a Brazilian beach: 800 mSv/yr, but people don’t live there.)

Several places are known in Iran, India and Europe where natural background radiation gives an annual dose of more than 100 mSv to people and up to 260 mSv (at Ramsar in Iran, where some 200,000 people are exposed to more than 10 mSv/yr). Lifetime doses from natural radiation range up to several thousand millisievert. However, there is no evidence of increased cancers or other health problems arising from these high natural levels. People living in Colorado and Wyoming have twice the annual dose as those in Los Angeles, but have lower cancer rates. Misasa hot springs in western Honshu, a Japan Heritage site, attracts people due to having high levels of radium (up to 550 Bq/L), with health effects long claimed, and in a 1992 study the local residents’ cancer death rate was half the Japan average.* (Japan J.Cancer Res. 83,1-5, Jan 1992) A study on 3000 residents living in an area with 60 Bq/m3 radon (about ten times normal average) showed no health difference. Hot springs in China have levels reaching 3270 Bq/L radon-222 (Liaoning sanatorium), 2720 Bq/L (Tanghe hot spring) and 230 Bq/L (Puxzhe hot spring), though associated exposure from airborne radon are low**.

* The waters are promoted as boosting the body’s immunity and natural healing power, while helping to relieve bronchitis and diabetes symptoms, as well as beautifying the skin. Drinking the water is also said to have antioxidant effects. (These claims are not known to be endorsed by any public health authority.)

** Chinese figures from Liu & Pan in NORM VII.

Radon is a naturally occurring radioactive gas resulting from the decay of uranium-238, which concentrates in enclosed spaces such as buildings and underground mines, particularly in early uranium mines where it sometimes became a significant hazard before the problem was understood and controlled by increased ventilation. Radon has decay products that are short-lived alpha emitters and deposit on surfaces in the respiratory tract during the passage of breathing air. At high radon levels, this can cause an increased risk of lung cancer, particularly for smokers. (Smoking itself has a very much greater lung cancer effect than radon.) People everywhere are typically exposed to around 0.2 mSv/yr, and often up to 3 mSv/yr, due to radon (mainly from inhalation in their homes) without apparent ill-effectd. Where deemed necessary, radon levels in buildings and mines can be controlled by ventilation, and measures can be taken in new constructions to prevent radon from entering buildings.

However, radon levels of up to 3700 Bq/m3 in some dwellings at Ramsar in Iran have no evident ill-effect. Here, a study (Mortazavi et al, 2005) showed that the highest lung cancer mortality rate was where radon levels were normal, and the lowest rate was where radon concentrations in dwellings were highest. The ICRP recommends keeping workplace radon levels below 300 Bq/m3, equivalent to about 10 mSv/yr. Above this, workers should be considered as occupationally exposed, and subject to the same monitoring as nuclear industry workers. The normal indoor radon concentration ranges from 10 to 100 Bq/m3, but may naturally reach 10,000 Bq/m3, according to UNEP.

Public exposure to natural radiatione

| Source of exposure | Annual effective dose (mSv) | ||

| Average | Typical range | ||

| Cosmic radiation | Directly ionizing and photon component | 0.28 | |

| Neutron component | 0.10 | ||

| Cosmogenic radionuclides | 0.01 | ||

| Total cosmic and cosmogenic | 0.39 | 0.3–1.0e | |

| External terrestrial radiation | Outdoors | 0.07 | |

| Indoors | 0.41 | ||

| Total external terrestrial radiation | 0.48 | 0.3-1.0e | |

| Inhalation | Uranium and thorium series | 0.006 | |

| Radon (Rn-222) | 1.15 | ||

| Thoron (Rn-220) | 0.1 | ||

| Total inhalation exposure | 1.26 | 0.2-10e | |

| Ingestion | K-40 | 0.17 | |

| Uranium and thorium series | 0.12 | ||

| Total ingestion exposure | 0.29 | 0.2-1.0e | |

| Total | 2.4 | 1.0-13 | |

US Naval Reactors’ average annual occupational exposure was 0.06 mSv per person in 2013, and no personnel have exceeded 20 mSv in any year in the 34 years to then. The average occupational exposure of each person monitored at Naval Reactors' facilities since 1958 is 1.03 mSv per year.

Effects of ionizing radiation

Some of the ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun is considered ionizing radiation, and provides a starting point in considering its effects. Sunlight UV is important in producing vitamin D in humans, but too much exposure produces sunburn and, potentially, skin cancer. Skin tissue is damaged, and that damage to DNA may not be repaired properly, so that over time, cancer develops and may be fatal. Adaptation from repeated low exposure can decrease vulnerability. But exposure to sunlight is quite properly sought after in moderation, and not widely feared.

Our knowledge of the effects of shorter-wavelength ionizing radiation from atomic nuclei derives primarily from groups of people who have received high doses. The main difference from UV radiation is that beta, gamma and X-rays can penetrate the skin. The risk associated with large doses of this ionizing radiation is relatively well established. However, the effects, and any risks associated with doses under about 200 mSv, are less obvious because of the large underlying incidence of cancer caused by other factors. Radiation protection standards assume that any dose of radiation, no matter how small, involves a possible risk to human health. However, at low levels of exposure, the body's natural mechanisms usually repair radiation damage to DNA in cells soon after it occurs (see following section on low-level radiation), whereas high-level irradiation overwhelms those repair mechanisms and is harmful. Dose rate is as important as overall dose.

The UN Scientific Commission on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) currently uses the term low dose to mean absorbed levels below 100 mGy but greater than 10 mGy, and the term very low dose for any levels below 10 mGy. High absorbed dose is defined as more than about 1000 mGy. For beta and gamma radiation, these figures can be taken as mSv equivalent dose.

| Some comparative whole-body radiation doses and their effects | |

| 2.4 mSv/yr | Typical background radiation experienced by everyone (average 1.5 mSv in Australia, 3 mSv in North America). |

|---|---|

| 1.5 to 2.5 mSv/yr | Average dose to Australian uranium miners and US nuclear industry workers, above background and medical. |

| Up to 5 mSv/yr | Typical incremental dose for aircrew in middle latitudes. |

| 9 mSv/yr | Exposure by airline crew flying the New York – Tokyo polar route. |

| 10 mSv/yr | Maximum actual dose to Australian uranium miners. |

| 10 mSv | Effective dose from abdomen & pelvis CT scan. |

| 20 mSv/yr | Current limit (averaged) for nuclear industry employees and uranium miners in most countries. (In Japan: 5 mSv per three months for women) |

| 50 mSv/yr | Former routine limit for nuclear industry employees, now maximum allowable for a single year in most countries (average to be 20 mSv/yr max). It is also the dose rate which arises from natural background levels in several places in Iran, India and Europe. |

| 50 mSv | Allowable short-term dose for emergency workers (IAEA). |

| 100 mSv | Lowest annual level at which increase in cancer risk is evident (UNSCEAR). Above this, the probability of cancer occurrence (rather than the severity) is assumed to increase with dose. No harm has been demonstrated below this dose. Allowable short-term dose for emergency workers taking vital remedial actions (IAEA). Dose from four months on international space station orbiting 350 km up. |

| 130 mSv/yr | Long-term safe level for public after radiological incident, measured 1 m above contaminated ground, calculated from published hourly rate x 0.6. Risk too low to justify any action below this (IAEA). |

| 170 mSv/wk | 7-day provisionally safe level for public after radiological incident, measured 1 m above contaminated ground (IAEA). |

| 250 mSv | Allowable short-term dose for workers controlling the 2011 Fukushima accident, set as emergency limit elsewhere. |

| 250 mSv/yr | Natural background level at Ramsar in Iran, with no identified health effects (Some exposures reach 700 mSv/yr). Maximum allowable annual dose in emergency situations in Japan (NRA). |

| 350 mSv/lifetime | Criterion for relocating people after Chernobyl accident. |

| 500 mSv | Allowable short-term dose for emergency workers taking life-saving actions (IAEA). |

| 680 mSv/yr | Tolerance dose level allowable to 1955 (assuming gamma, X-ray and beta radiation). |

| 700 mSv/yr | Suggested threshold for maintaining evacuation after nuclear accident. (IAEA has 880 mSv/yr over one month as provisionally safe. |

| 800 mSv/yr | Highest level of natural background radiation recorded, on a Brazilian beach. |

| 1000 mSv short-term | Assumed to be likely to cause a fatal cancer many years later in about 5 of every 100 persons exposed to it (i.e. if the normal incidence of fatal cancer were 25%, this dose would increase it to 30%). Highest reference level recommended by ICRP for rescue workers in emergency situation. |

| 1000 mSv short-term | Threshold for causing (temporary) radiation sickness (Acute Radiation Syndrome) such as nausea and decreased white blood cell count, but not death. Above this, severity of illness increases with dose. |

| 4000-5000 mSv short-term | Would kill about half those receiving it as whole body dose within a month. (However, this is only twice a typical daily therapeutic dose applied to a very small area of the body over 4 to 6 weeks or so to kill malignant cells in cancer treatment.) |

| 8000 mSv short-term | At this level of radiation exposure, the survival rates are at or close to zero, irrespective of level of medical care. |

The main expert body on radiation effects is the UN Scientific Commission on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR), set up in 1955 and reporting to the UN General Assembly. It involves scientists from over 20 countries and publishes its findings in major reports. The UNSCEAR 2006 report dealt broadly with the Effects of Ionizing Radiation. Another valuable report, titled Low-level Radiation and its Implications for Fukushima Recovery, was published in June 2012 by the American Nuclear Society.

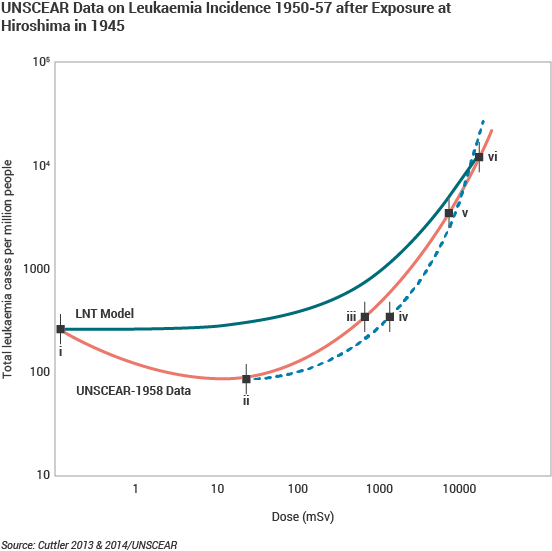

In 2012 UNSCEAR reported to the UN General Assembly on radiation effects. It had been asked in 2007 "to clarify further the assessment of potential harm owing to chronic low-level exposures among large populations and also the attributability of health effects" to radiation exposure. It said that while some effects from high acute doses were clear, others including hereditary effects in human populations were not, and could not be attributed to exposure, and that this was especially true at low levels. "In general, increases in the incidence of health effects in populations cannot be attributed reliably to chronic exposure to radiation at levels that are typical of the global average background levels of radiation." Furthermore, multiplying very low doses by large numbers of individuals does not give a meaningful result regarding health effects. UNSCEAR also addressed uncertainties in risk estimation relating to cancer, particularly the extrapolations from high-dose to low-dose exposures and from acute to chronic and fractionated exposures. Earlier (1958) UNSCEAR data for leukaemia incidence among Hiroshima survivors suggested a threshold of about 400 mSv for harmful effects.

Epidemiological studies continue on the survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, involving some 76,000 people exposed at levels ranging up to more than 5,000 mSv. These have shown that radiation is the likely cause of several hundred deaths from cancer, in addition to the normal incidence found in any populationf. From this data the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) and others estimate the fatal cancer risk as 5% per sievert exposure for a population of all ages – so one person in 100 exposed to 200 mSv could be expected to develop a fatal cancer some years later. In Western countries, about a quarter of people die from cancers, with smoking, dietary factors, genetic factors and strong sunlight being among the main causes. About 40% of people are expected to develop cancer during their lifetime even in the absence of radiation exposure beyond normal background levels. Radiation is a weak carcinogen, but undue exposure can certainly increase health risks.

In 1990, the US National Cancer Institute (NCI) found no evidence of any increase in cancer mortality among people living near to 62 major nuclear facilities. The NCI study was the broadest of its kind ever conducted and supported similar studies conducted elsewhere in the USA as well as in Canada and Europe.g

About 60 years ago it was discovered that ionizing radiation could induce genetic mutations in fruit flies. Intensive study since then has shown that radiation can similarly induce mutations in plants and test animals. However there is no evidence of inherited genetic damage to humans from radiation, even as a result of the large doses received by atomic bomb survivors in Japan.

In a plant or animal cell the material (DNA) which carries genetic information necessary to cell development, maintenance and division is the critical target for radiation. Much of the damage to DNA is repairable, but in a small proportion of cells the DNA is permanently altered. This may result in death of the cell or development of a cancer, or in the case of cells forming gonad tissue, alterations which continue as genetic changes in subsequent generations. Most such mutational changes are deleterious; very few can be expected to result in improvements.

The relatively low levels of radiation allowed for members of the public and for workers in the nuclear industry are such that any increase in genetic effects due to nuclear power will be imperceptible and almost certainly non-existent. Radiation exposure levels are set so as to prevent tissue damage and minimize the risk of cancer. Experimental evidence indicates that cancers are more likely than inherited genetic damage.

Some 75,000 children born of parents who survived high radiation doses at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 have been the subject of intensive examination. This study confirms that no increase in genetic abnormalities in human populations is likely as a result of even quite high doses of radiation. Similarly, no genetic effects are evident as a result of the Chernobyl accident.

Life on Earth commenced and developed when the environment was certainly subject to several times as much radioactivity as it is now, so radiation is not a new phenomenon. If there is no dramatic increase in people's general radiation exposure, there is no evidence that health or genetic effects from radiation could ever become significant.

Time perspective

The health effects of exposure both to radiation and to chemical cancer-inducing agents or toxins must be considered in relation to time. There is cause for concern not only about the effects on people presently living, but also about the cumulative effects that actions today might have over many generations.

Some radioactive materials decay to safe levels within days, weeks or a few years, while others maintain their radiotoxicity for a long time. While cancer-inducing and other toxins can also remain harmful for long periods, some (e.g. heavy metals such as mercury, cadmium and lead) maintain their toxicity forever. The essential task for those in government and industry is to prevent excessive amounts of such toxins harming people, now or in the future. Standards are set in the light of research on environmental pathways by which people might ultimately be affected.

Low-level radiation effects

The so-called linear no-threshold (LNT) model assumes that the demonstrated relationships between radiation dose and adverse effects at high levels of exposure also applies to low levels and provides the (deliberately conservative) basis of occupational health and other radiation protection standards.

The ICRP recommends that the LNT model should be assumed for the purpose of optimising radiation protection practices, but that it should not be used for estimating the health effects of exposures to small radiation doses received by large numbers of people over long periods of time. At low levels of exposure, the body's natural mechanism repairs radiation and other damage to cells soon after it occurs, as with exposure to other external agents at low levels.

A November 2009 technical report from the Electric Power Research Institute in USA drew upon more than 200 peer-reviewed publications on effects of low-level radiation and concluded that the effects of low dose-rate radiation are different and that "the risks due to [those effects] may be over-estimated" by the linear hypothesis1. "From an epidemiological perspective, individual radiation doses of less than 100 mSv in a single exposure are too small to allow detection of any statistically significant excess cancers in the presence of naturally occurring cancers. The doses received by nuclear power plant workers fall into this category because exposure is accumulated over many years, with an average annual dose about 100 times less than 100 mSv". It quoted the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission that "since 1983, the US nuclear industry has monitored more than 100,000 radiation workers each year, and no workers have been exposed to more than 50 mSv in a year since 1989." A 2012 Massachusetts Institute of Technology study2 exposing mice to low-dose rate radiation for an extended period showed no signs of DNA damage, though a control group receiving the same dose acutely did show damage.

There is some in vitro evidence of a beneficial effect from low-level radiation (up to about 10 mSv/yr), a phenomenon which is called hormesis. This effect may arise as a result of an adaptive response by the body's cells, in a similar way to physical exercise, where small and moderate amounts have a positive effect, whereas too much would have detrimental effects. In the case of carcinogens such as ionizing radiation, the beneficial effect would be seen both in a lower incidence of cancer and a resistance to the effects of higher doses. However, there is considerable uncertainty whether there is a hormetic effect in relation to radiation and, if such an effect actually exists, how large it would be. There is currently no conclusive in vivo evidence to support hormesis. Further research is under way and the debate around the actual health effects of low-dose radiation continues. Meanwhile standards for radiation exposure continue to be deliberately conservative.

In the USA, The Low-Dose Radiation Research Act of 2015 calls for an assessment of the current status of US and international low-dose radiation research. It also directs the National Academy of Sciences to “formulate overall scientific goals for the future of low-dose radiation research in the United States” and to develop a long-term research agenda to address those goals. The Act arises from a letter from a group of health physicists who pointed out that the limited understanding of low-dose health risks impairs the nation’s decision-making capabilities, whether in responding to radiological events involving large populations such as the 2011 Fukushima accident or in areas such as the rapid increase in radiation-based medical procedures, the cleanup of radioactive contamination from legacy sites and the expansion of civilian nuclear energy.

Fear of radiation effects

The main effects arising from the exposure to low-level radiation, especially following nuclear accidents, are not from the radiation itself, but are psychosocial in nature. Following the Chernobyl and Fukushima Daiichi accidents, there were sharp increases in a range of negative mental health impacts, including stress, anxiety, and depression. Substance abuse and increased rates of suicide have also been reported amongst certain populations. After the Chernobyl accident, pregnant women in some parts of Europe sought to terminate their pregnancies, despite there being no risk to the foetus as any radiation dose would be far below those required to cause any harm. The fear of radiation also affects government decisions which might have detrimental impacts. Following the Fukushima Daiichi accident, the Japanese government's decision to evacuate vulnerable people in a hurried manner, and maintaining these evacuations, played a significant role in the deaths of more than 2200 people, whereas the radiation levels were too low to cause any fatalities. Furthermore, concerns about low doses of radiation from CT scans and X-rays may lead to suffering and deaths from avoided or delayed diagnosis. In addition, the therapeutic benefits of nuclear medicine greatly outweigh any harm that might come from the radiation exposure involved.

Limiting exposure

Public dose limits for exposure from uranium mining or nuclear plants are usually set at 1 mSv/yr above background.

In most countries the current maximum permissible dose to radiation workers is 20 mSv per year averaged over five years, with a maximum of 50 mSv in any one year. This is over and above background exposure, and excludes medical exposure. The value originates from the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), and is coupled with the requirement to keep exposure as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) – taking into account social and economic factors.

Radiation protection at uranium mining operations and in the rest of the nuclear fuel cycle is tightly regulated, and levels of exposure are monitored.

There are four ways in which people are protected from identified radiation sources:

- Limiting time. In occupational situations, dose is reduced by limiting exposure time.

- Distance. The intensity of radiation decreases with distance from its source.

- Shielding. Barriers of lead, concrete or water give good protection from high levels of penetrating radiation such as gamma rays. Intensely radioactive materials are therefore often stored or handled under water, or by remote control in rooms constructed of thick concrete or lined with lead.

- Containment. Highly radioactive materials are confined and kept out of the workplace and environment. Nuclear reactors operate within closed systems with multiple barriers which keep the radioactive materials contained.

UNEP notes: “While the release of radon in underground uranium mines makes a substantial contribution to occupational exposure on the part of the nuclear industry, the annual average effective dose to a worker in the nuclear industry overall has decreased from 4.4 mSv in the 1970s to about 1 mSv today. However, the annual average effective dose to a coal miner is still about 2.4 mSv and for other miners about 3 mSv." The mining figures are probably for underground situations.

About 23 million workers worldwide are monitored for radiation exposure, and about 10 million of these are exposed to artificial sources, mostly in the medical sector where the annual dose averages 0.5 mSv.

Standards and regulation of radiation exposure

Radiation protection standards are based on the conservative assumption that the risk is directly proportional to the dose, even at the lowest levels, though there is no actual evidence of harm at low levels, below about 100 mSv as short-term dose. However, the standard assumption – the linear no-threshold (LNT) model – discounts the contribution of any such thresholds and is recommended for practical radiation protection purposes only, such as setting allowable levels of radiation exposure of individuals.

LNT was first accepted by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) in 1955, when scientific knowledge of radiation effects was less, and then in 1959 by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) as a philosophical basis for radiological protection at low doses, stating outright that “Linearity has been assumed primarily for purposes of simplicity, and there may or may not be a threshold dose”. (Above 100 mSv acute dose there is some scientific evidence for linearity in dose-effect.) From 1934 to 1955 a tolerance dose limit of 680 mSv/yr was recommended by the ICRP, and no evidence of harm from this – either cancer or genetic – had been documented.

The LNT hypothesis cannot properly be used for predicting the consequences of an actual exposure to low levels of radiation and it has no proper role in low-dose risk assessment. For example, LNT suggests that, if the dose is halved from a high level where effects have been observed, there will be half the effect, and so on. This would be very misleading if applied to a large group of people exposed to trivial levels of radiation and even at levels higher than trivial it could lead to inappropriate actions to avert the doses.

Much of the evidence which has led to today's standards derives from the atomic bomb survivors in 1945, who were exposed to high doses incurred in a very short time. In setting occupational risk estimates, some allowance has been made for the body's ability to repair damage from small exposures, but for low-level radiation exposure the degree of protection from applying LNT may be misleading. At low levels of radiation exposure the dose-response relationship is unclear due to background radiation levels and natural incidence of cancer. However, the Hiroshima survivor data published in 1958 by UNSCEAR for leukaemia (see Appendix) actually shows a reduction in incidence by a factor of three in the dose range 1 to 100 mSv. The threshold for increased risk here is about 400 mSv. This is very significant in relation to concerns about radiation exposure from contaminated areas after the Chernobyl and Fukushima accidents.

The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), set up in 1928, is a body of scientific experts and a respected source of guidance on radiation protection, though it is independent and not accountable to governments or the UN. Its recommendations are widely followed by national health authorities, the EU and the IAEA. It retains the LNT hypothesis as a guiding principle.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has published international radiation protection standards since 1962. It is the only UN body with specific statutory responsibilities for radiation protection and safety. Its Safety Fundamentals are applied in basic safety standards and consequent Regulations. However, the UN Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) set up in 1955 is the most authoritative source of information on ionizing radiation and its effects.

In any country, radiation protection standards are set by government authorities, generally in line with recommendations by the ICRP, and coupled with the requirement to keep exposure as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) – taking into account social and economic factors. The authority of the ICRP comes from the scientific standing of its members and the merit of its recommendations.

The three key points of the ICRP's recommendations are:

- Justification. No practice should be adopted unless its introduction produces a positive net benefit.

- Optimisation. All exposures should be kept as low as reasonably achievable, economic and social factors being taken into account.

- Limitation. The exposure of individuals should not exceed the limits recommended for the appropriate circumstances.

National radiation protection standards are framed for both Occupational and Public exposure categories.

The ICRP recommends that the maximum permissible dose for occupational exposure should be 20 millisievert per year averaged over five years (i.e. 100 millisievert in 5 years) with a maximum of 50 millisievert in any one year. For public exposure, 1 millisievert per year averaged over five years is the limit. In both categories, the figures are over and above background levels, and exclude medical exposure.i

Post-accident exposure

These low exposure levels are achievable for normal nuclear power and medical activities, but where an accident has resulted in radioactive contamination their application has no net health benefit. There is a big difference between what is desirable in the normal planned operation of any plant, and what is tolerable for dealing with the effects of an accident. Here, restrictive dose limits will limit flexibility in managing the situation and thus their application may increase other health risks, or even result in major adverse health effects, as near Fukushima since March 2011 (see earlier endnote). The objective needs to be to minimize the risks and harm to the individual and population overall, rather than focusing on radiation in isolation.

This is recognised to some extent in the occupational health limits set for cleaning up such situations: the IAEA sets 100 mSv as the allowable short-term dose for emergency workers taking vital remedial actions, and 500 mSv as allowable short-term dose for emergency workers taking life-saving actions. At Fukushima, 250 mSv was set as the allowable short-term dose for workers controlling the disabled reactors during 2011. Following NRA consideration of the Fukushima experience, as well as overseas standards and the science, 250 mSv is now the proposed allowable dose in emergency situations in Japan from April 2016.

But even these levels are low, and there has been no corresponding allowance for neighbouring members of the public – ALARA was the only reference criterion regardless of its collateral effects due to prolonging the evacuation beyond a few days. When making decisions on evacuations, all health risks (not just radiation exposure) should be addressed, as focusing on the minimization of one risk (which might already be small, or even non-existant) can lead to other risks being increased. This was evident at Fukushima, as the death toll and trauma from evacuation were very much greater than the risks of elevated radiation exposure after the first few days.

This led to the IAEA in May 2013 publishing allowable dose rates for members of the public living normally in affected areas, measured 1m above the contaminated ground. A level of 220 mSv/yr over a full year is "safe for everyone" providing any ingested radioactivity is safe. In the shorter term, at 40 times this level, 170 mSv for one week is provisionally safe, and at four times the yearly level – 880 mSv – is provisionally safe for one month.

This has also led to calls for ALARA to be replaced with other concepts when dealing with emergency or existing high exposure situations, based on the scientific evidence available. One such proposal is the AHANE – as high as naturally existent – concept. AHANE builds on the evidence pertaining to high natural background radiation exposures across the world, where large populations are exposed to very high background radiation levels (of the order of 10-100 times greater than the average global background level) without discernable negative health effects. In Ramsar, Iran, about 2000 people are exposed to at least 250 mSv/yr with no adverse effect. In Guarapari, Brazil (population 73,000), Kerala, India (population 100,000), and Yangjiang, China (population 80,000), the average exposures are about 50 mSv/yr, 38 mSv/yr and 35 mSv/yr respectively. In all cases, the residents have life expectancies at least as long as their national peers, and cancer rates slightly lower than fellow countrymen.

Some physicists have gone further and proposed the AHARS – as high as relatively safe – concept, which would be similar to the tolerance doses system that was in use from the 1920s until the 1950s. AHARS would see the exposure limits increase to around 1000 mSv/yr or 100 mSv per month. This, however, has very little support in the scientific literature and there is evidence suggesting that radiation exposures above 100 mSv slightly increase lifetime risk for developing cancer. Nevertheless, it is clear that the current ALARA concept does not serve its original purpose, and especially not in the context of radiological accidents where more harm is caused by focusing excessively on radiation risks, at the expense of taking sufficient measures to mitigate other risks.

Despite this, in March 2011, soon after the Fukushima accident, the ICRP said that it “continues to recommend reference levels of 500 to 1000 mSv to avoid the occurrence of severe deterministic injuries for rescue workers involved in an emergency exposure situation.” For members of the public in such situations, it recommends “reference levels for the highest planned residual dose in the band of 20 to 100 millisieverts (mSv)”, dropping to 1 to 20 mSv/yr when the situation is under control.

Nuclear fuel cycle radiation exposures

The average annual radiation dose to employees at uranium mines (in addition to natural background) is around 2 mSv (ranging up to 10 mSv). Natural background radiation is about 2 mSv. In most mines, keeping doses to such low levels is achieved with straightforward ventilation techniques coupled with rigorously enforced procedures for hygiene. In some Canadian mines, with very high-grade ore, sophisticated means are employed to limit exposure. (See also information page on Occupational Safety in Uranium Mining.) Occupational doses in the US nuclear energy industry – conversion, enrichment, fuel fabrication and reactor operation – average less than 3 mSv/yr.

Reprocessing plants in Europe and Russia treat used fuel to recover useable uranium and plutonium and separate the highly radioactive wastes. These facilities employ massive shielding to screen gamma radiation in particular. Manual operations are carried by operators behind lead glass using remote handling equipment.

In mixed oxide (MOX) fuel fabrication, little shielding is required, but the whole process is enclosed with access via gloveboxes to eliminate the possibility of alpha contamination from the plutonium. Where people are likely to be working alongside the production line, a 25mm layer of perspex shields neutron radiation from the Pu-240. (In uranium oxide fuel fabrication, no shielding is required.)

Interestingly, due to the substantial amounts of granite in their construction, many public buildings including Australia's Parliament House and New York Grand Central Station, would have some difficulty in getting a licence to operate if they were nuclear power stations.

Historical cases of accidental radiation exposure

Kyshtym, Russia (1957) – military nuclear reprocessing plant

There was a major chemical accident at Mayak Chemical Combine (then known as Chelyabinsk-40) near Kyshtym in Russia in 1957. This plant had been built in haste in the late 1940s for military purposes. The failure of the cooling system for a tank storing many tonnes of dissolved nuclear waste resulted in an ammonium nitrate explosion with a force estimated at about 75 tonnes of TNT (310 GJ). Most of the 740-800 PBq of radioactive contamination settled out nearby and contributed to the pollution of the Techa River, but a plume containing 80 PBq of radionuclides spread hundreds of kilometres northeast. The affected area was already very polluted – the Techa River had previously received about 100 PBq of deliberately dumped waste, and Lake Karachay had received some 4000 PBq. This 'Kyshtym accident’ killed perhaps 200 people and the radioactive plume affected thousands more as it deposited particularly Cs-137 and Sr-90. It was rated as level 6 on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES).

Many people received doses up to 400 mSv at relatively low dose rates from liquid wastes released into the river. This population has shown an increase in cancer rates at levels above 200 mSv. But below this level, cancer incidence falls below the LNT expectations.

Nuclear Reactor Testing Station, USA (1961) – military research reactor

Due to the improper withdrawal of control rods, the Stationary Low-Power Reactor Number One (SL-1) experienced a steam explosion and core meltdown. The accident resulted in the deaths of the three operators. Whilst the operators died due to the physical trauma of the explosion, they were exposed to very high levels of radiation which would have been fatal.

Mexico City, Mexico (1962) – orphan source

A young boy took home an unshielded cobalt-60 radiography source, with the ensuing exposure resulting in nine people suffering ARS, of which four died.

Riverside Methodist Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, USA (1974-1976) – radiotherapy

A radiotherapy machine was calibrated based on an incorrect decay curve, which resulted in ten patients dying and a further 78 being injured due to overexposure.

Three Mile Island, USA (1979) – nuclear power reactor

The accident at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in March 1979 resulted in a few individuals near the plant receiving very low doses of radiation, well below the regulatory thresholds. Subsequent scientific studies have found no evidence of any harm resulting from the accident. INES rating 5.

Mohammedia, Morocco (1984) – orphan source

An iridium-192 source, used for industrial radiography, was removed from its shielded container and taken home by a worker. 11 people suffered from ARS, of which eight died.

USA/Canada (1985-1987) – radiotherapy

A software failure and a fundamental design flaw in the Therac-25 medical irradiation device resulted in at least six accidents where 100 times the beta radiation dose intended was delivered. Six people suffered from ARS, of which three died.

Chernobyl, Ukraine (1986) – nuclear power reactor

Immediately after the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster in 1986, many people received large doses. Apart from the residents of nearby Pripyat, who were evacuated within two days, some 24,000 people living within 15 km of the plant received an average of 450 mSv before they were evacuated. A total of 5200 PBq of radioactivity (iodine-131 equivalent) was released.

In June 1989, a group of experts from the World Health Organization agreed that an incremental long-term dose of 350 mSv should be the criterion for relocating people affected by the 1986 Chernobyl accident. This was considered a "conservative value which ensured that the risk to health from this exposure was very small compared with other risks over a lifetime". (For comparison, background radiation averages about 150-200 mSv over a lifetime in most places.)

Out of the 134 severely exposed workers and firemen, 28 of the most heavily exposed died as a result of acute radiation syndrome (ARS) within three months of the accident. Of these, 20 were from the group of 21 that had received over 6.5 Gy, seven (out of 22) had received between 4.2 and 6.4 Gy, and one (out of 50) from the group that had received 2.2-4.1 Gy.3 A further 19 died in 1987-2004 from different causes (see information page on Chernobyl Accident Appendix 2: Health Impacts).

Regarding the emergency workers with doses lower than those causing ARS symptoms, a 2006 World Health Organization report4 referred to studies carried out on 61,000 emergency Russian workers where a total of 4995 deaths from this group were recorded during 1991-1998. "The number of deaths in Russian emergency workers attributable to radiation caused by solid neoplasms and circulatory system diseases can be estimated to be about 116 and 100 cases respectively." Furthermore, although no increase in leukaemia is discernible yet, "the number of leukaemia cases attributable to radiation in this cohort can be estimated to be about 30." Thus, 4.6% of the number of deaths in this group are attributable to radiation-induced diseases. (The estimated average external dose for this group was 107 mSv.)

The report also links the accident to an increase in thyroid cancer in children: "During 1992-2000, in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, about 4000 cases of thyroid cancer were diagnosed in children and adolescents (0-18 years), of which about 3000 occurred in the age group of 0-14 years. For 1152 thyroid cancer patient cases diagnosed among Chernobyl children in Belarus during 1986-2002, the survival rate is 98.8%. Eight patients died due to progression of their thyroid cancer and six children died from other causes. One patient with thyroid cancer died in Russia."

There has been no increase attributable to Chernobyl in congenital abnormalities, adverse pregnancy outcomes or any other radiation-induced disease in the general population either in the contaminated areas or further afield.

Reports two decades after the accident make it clear that the main health effects from the accident are due to the evacuation of many people coupled with fear engendered, and thousands have died from suicide, depression and alcoholism. The 2006 Chernobyl Forum report said that people in the area suffered a paralysing fatalism due to myths and misperceptions about the threat of radiation, which contributed to a culture of chronic dependency. Some "took on the role of invalids." Mental health coupled with smoking and alcohol abuse is a very much greater problem than radiation, but worst of all at the time was the underlying level of health and nutrition. Psycho-social effects among those affected by the accident are similar to those arising from other major disasters such as earthquakes, floods and fires.

After the shelterf was built over the destroyed reactor at Chernobyl, a team of about 15 engineers and scientists was set up to investigate the situation inside it. Over several years they repeatedly entered the ruin, accumulating individual doses of up to 15,000 mSv. Daily dose was mostly restricted to 50 mSv, though occasionally it was many times this. None of the men developed any symptoms of radiation sickness, but they must be considered to have a considerably increased cancer risk. INES rating 7.

Goiania, Brazil (1987) – orphan source

In 1987 at Goiania6 in Brazil, a discarded radiotherapy source stolen from an abandoned hospital and broken open caused four deaths, 20 cases of radiation sickness and significant contamination of many more. The teletherapy source contained 93 grams of caesium-137 (51 TBq) encased in a shielding canister 51 mm diameter and 48 mm long made of lead and steel, with an iridium window. Various people came in contact with the source over two weeks as it was relayed to a scrapyard, and some were seriously affected. The four deaths (4-5 Sv dose) were family and employees of the scrapyard owner, and 16 others received more than 500 mSv dose. Overall 249 people were found to have significant levels of radioactive material in their bodies. In the 25 years since 1987 there have been zero cancers from radiation among those 249 people affected at Goiania, in spite of the ingestion of up to 100 MBq giving doses as high as 625 mSv/month (8 individuals had higher activity than 100 MBq internally of whom 4 died of acute radiation syndrome but none of cancer). Two healthy babies were born, one to a mother among the most highly contaminated. However fear of the contamination has been the cause of severe stress and depression. In March 2012 Yukiya Amano, the Director General of the IAEA, described Goiania as the best illustration of the effect of a terrorist dirty bomb – a few deaths but widespread fear and stress. INES rating 5.

Zaragoza, Spain (1990) – radiotherapy

27 cancer patients were exposed to very high doses from an incorrectly repaired GE electron accelerator, of whom 15 died as a consequence of radiation overexposure, and a further two died with radiation as a major contributor.

San Jose, Costa Rica (1996) – radiotherapy

115 people received an overdose of radiation from a miscalibrated cobalt-60 radiotherapy unit. According to the IAEA report regarding the incident, there were seven fatalities – three as a direct consequence of the radiation exposure and four where radiation played a contributing role. 46 further patients suffered from adverse health consequences due to overexposure.

Tokai-mura, Japan (1999) – criticality accident

During fuel preparations at the Tokai-mura facility a criticality accident took place. Two of the three operators died due to radiation exposure. Approximately 200 residents were temporarily evacuated, the vast majority receiving extremely low doses.

Samut Prakan, Thailand (2000) – orphan source

An orphan cobalt-60 source was opened in a scrap metal yard, which resulted in ten people being hospitalized due to developing ARS, of which three subsequently died.

Panama City, Panama (2000-2001) – radiotherapy

28 people received an overdose of radiation when receiving radiotherapy due to the use of a treatment protocol which had not been validated and incorrect data entry. Three patients died as a result of overexposure, with another two deaths probably being related to radiation. Two of the deaths were not attributable and one patient died due to their cancer. A further 20 patients survived, but most sustaining radiation-related injuries.

Fleurus, Belgium (2006) – commercial irradiation

A worker at the Institute for Radioelements (IRE) in Fleurus received a high radiation dose (between 4.2-4.6 Gy) from a cobalt-60 source used for medical device sterilization, resulting in the worker developing ARS.

Mayapuri, India (2010) – orphan source

A university irradiator was sold to a scrap metal dealer and was subsequently disassembled, with the cobalt-60 source being cut into several smaller pieces. Eight people were hospitalized with ARS, of which one died.

Fukushima Dai-ichi, Japan (2011) – nuclear power reactor

The March 2011 accident at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan released about 940 PBq (iodine-131 equivalent) of radioactive material, mostly on days 4 to 6 after the tsunami. In May 2013 UNSCEAR reported that "Radiation exposure following the nuclear accident at Fukushima Daiichi did not cause any immediate health effects. It is unlikely to be able to attribute any health effects in the future among the general public and the vast majority of workers." The only exception are the 146 emergency workers that received radiation doses of over 100 mSv during the crisis.5 Thyroid doses in children were significantly lower than from the Chernobyl accident. Some 160,000 people were evacuated as a precautionary measure. The highest internal radioactivity from ingestion was 12 kBq, some 1000 times less than the level causing adverse health effects at Goiania (see below).

Certainly the main radiation exposure was to workers on site, and the 146 with doses over 100 mSv will be monitored closely for "potential late radiation-related health effects at an individual level." Six of them had received over 250 mSv – the limit set for emergency workers there, apparently due to inhaling iodine-131 fume early on. There were around 250 workers on site each day. INES rating 7.

Stamboliyski, Bulgaria (2011) – commercial irradiation

During planned operations of a gamma irradiation facility with cobalt-60 sources, a device already recharged with sources had been taken out, instead of an empty one due to personnel error. Five workers were exposed to doses between 1.23-5.63 Gy and all developed ARS.

Appendix

Data points from the left:

i) A control group of 32,963 people over 3 km from the hypocenter. 273 people per million developed leukaemia.

ii) 32,692 people between 2 and 3 km of the hypocenter, with estimated average exposure of about 20 mSv. 92 people per million developed leukaemia.

iii) and iv) 20,113 people between 1.5 and 2 km of the hypocenter, where average doses “were greater than” 500mSv. The left data point (iii) represents calculated radiation exposure for that zone; the right (iv) represents what is thought to be more a more accurate dose, given the cohort's other radiation-induced symptoms. 398 people per million developed leukaemia.

v) 8810 people between 1 and 1.5 km of the hypocenter, with estimated average exposure of about 5000 mSv. 3746 people per million developed leukaemia.

vi) 1241 survivors less than 1 km from the hypocenter, where over 50,000 were killed. 12,087 people per million developed leukaemia.

The latency period for leukaemia is less than six months. NB this is a log-log graph, and the green line would otherwise be straight.

Further Information

Notes

a. Three of the main radioactive decay series relevant to nuclear energy are those of uranium and thorium. These series are shown in the Figure at www.world-nuclear.org/uploadedImages/org/info/radioactive_decay_series.png [Back]

b. The concentration of radon decay progeny (RnDP) is measured in working levels or in microjoules of ultimately-delivered alpha energy per cubic metre of air. One 'working level' (WL) is approximately equivalent to 3700 Bq/m3 of Rn-222 in equilibrium with its decay progeny (the main two of which are the very short-lived alpha-emitters), or to 20.7 μJ/m3. The former assumes still air, not proper ventilation. One working level month (WLM) is the dose from breathing one WL for 170 hours, and the former occupational exposure limit was 4 WLM/yr. Today the ICRP recommended limit is 3.5 μJ/m3, which is a measure of the actual RnDP situation in whatever conditions of ventilation prevail. It is generally equivalent to about 2000 hours per year exposure to 3000 Bq/m3 of radon in a ventilated mine where the radon is removed and so is not in equilibrium with its decay progeny. [Back]

c. At an altitude of 30,000 feet, the dose rate is 3-4 μSv per hour at the latitudes of North America and Western Europe. At 40,000 feet, the dose rates are about 6.5-8 μSv per hour. Other measured rates were 6.6 μSv per hour during a Paris-Tokyo (polar) flight and 9.7 μSv per hour on the Concorde, while a study on Danish flight crew showed that they received up to 9 mSv/yr. [Back]

d. A background radon level of 40 Bq/m3 indoors and 6 Bq/m3 outdoors, assuming an indoor occupancy of 80%, is equivalent to a dose rate of 1 mSv/yr and is the average for most of the world's inhabitants. Exposure levels of less than 200 Bq/m3 (and arguably much more) are not considered hazardous unless public health concerns are based on LNT, contrary to ICRP recommendations. [Back]

e.

Range for cosmic and cosmogenic dose for sea level to high ground elevation.

Range for external terrestrial radiation depends on radionuclide composition of soil and building material.

Range for inhalation exposure depends on indoor accumulation of radon gas.

Range for ingestion exposure depends on radionuclide composition of foods and drinking water.

Source: Table 12 from Exposures of the Public and Workers from Various Sources of Radiation, Annex B to Volume I of the 2008 United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation Report to the General Assembly, Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation, available on the UNSCEAR 2008 Report Vol. I webpage (www.unscear.org/unscear/en/publications/2008_1.html) [Back]

f. The actual doses received by atomic bomb survivors are uncertain. Also much of the radiation then was from neutrons, though gamma radiation is the prime concern for radiation protection. Some 65 years after the acute exposure it can be seen that cancer rate in the irradiated survivors is lower than the controls, and lower than in the Japanese population as a whole8. [Back]

g. In the UK there are significantly elevated childhood leukaemia levels near Sellafield as well as elsewhere in the country. The reasons for these increases, or clusters, are unclear, but a major study of those near Sellafield has ruled out any contribution from nuclear sources. Apart from anything else, the levels of radiation at these sites are orders of magnitude too low to account for the excess incidences reported. However, studies are continuing in order to provide more conclusive answers. [Back]

i. The most recent revision of the ICRP's recommendations were issued in 2007 (Publication 103) which replaced the 1990 recommendations (Publication 60) without making any changes to the dose limits for occupational or public exposure. These values are also implemented by the IAEA in its Basic Safety Standard. [Back]

References

1. Program on Technology Innovation: Evaluation of Updated Research on the Health Effects and Risks Associated with Low-Dose Ionizing Radiation, Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), Palo Alto, California, USA, 1019227 (November 2009). A much-quoted 2005 study of low-dose exposure of nuclear workers – Cardis et al, Risk of cancer after low doses of ionising radiation: retrospective cohort study in 15 countries, British Medical Journal (BMJ 2005; 331:77) – depended heavily on Canadian data which was subsequently withdrawn by CNSC in 2011. Without that flawed data, the study showed no increased risk from low-dose radiation.[Back]

2. Werner Olipitz et al, Integrated Molecular Analysis Indicates Undetectable Change in DNA Damage in Mice after Continuous Irradiation at ~ 400-fold Natural Background Radiation, Environmental Health Perspectives (2012 August 2012), 120(8), 1130-1136. See also MIT news article, A new look at prolonged radiation exposure (15 May 2012) [Back]

3. Table 11 from Exposures and effects of the Chernobyl accident, Annex J to Volume II of the 2000 United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation Report to the General Assembly, available on the UNSCEAR 2000 Report Vol. II webpage (www.unscear.org/unscear/en/publications/2000_2.html) [Back]

4. Health Effects of the Chernobyl Accident and Special Health Care Programmes, Report of the UN Chernobyl Forum, Expert Group "Health", World Health Organization, 2006 (ISBN: 9789241594172). [Back]

5. UNSCEAR General Assembly reports and resolutions webpage [Back]

6. International Atomic Energy Agency, The Radiological Accident in Goiania (1988) [Back]

7. Wm. Robert Johnston, Database of radiological incidents and related events, Fleurus irradiator accident, 2006 [Back]

8. T. D. Luckey, Nuclear law stands on thin ice, International Journal of Nuclear Law, Vol 2, No 1, P 33-65 (2008) [Back]

General sources

Prof Bernard L. Cohen, Validity of the Linear No-Threshold Theory of Radiation Carcinogenesis at Low Doses, presented at the 23rd Annual International Symposium of The Uranium Institute (now World Nuclear Association) held in London, UK in September 1998.

Allison W. 2009. Radiation and Reason: Impact of Science on a Culture of Fear. York Publishing Services. UK. Website http://www.radiationandreason.com

Allison W. 2011. Risk Perception and Energy Infrastructure. Evidence submitted to UK Parliament. Commons Select Committee. Science and Technology. December 22.

American Nuclear Society, Low-level Radiation and its Implications for Fukushima Recovery (57 MB), President's Special Session, June 2012. http://db.tt/GYz46cLe (14 MB).

Cuttler, J.M., Commentary on Fukushima and Beneficial Effects of Low Radiation, Canadian Nuclear Society Bulletin, 34(1):27-32 (2013) also Dose-Response 10:473-479, 2012.

Cuttler, J.M., Commentary on the Appropriate Radiation Level for Evacuations, Dose-Response, 10:473-479, 2012.

Cuttler, J.M. & Pollycove, M, Nuclear Energy and Health: and the benefits of low-dose radiation hormesis, Dose-Response 7:52-89, 2009.

Cuttler, J.M., Remedy for Radiation Fear – Discard the Politicized Science, Canadian Nuclear Society Bulletin, Dec 2013

Cuttler, J.M., Leukemia incidence of 96,000 Hiroshima atomic bomb survivors is compelling evidence that the LNT model is wrong, Arch Toxicol, Jan 2014

Radiation and Reason website

Position Statements webpage of the Health Physics Society (www.hps.org)

Health Physics Society, 2013, Radiation and Risk: Expert Perspectives.

Health Physics website of the University of Michigan (www.umich.edu)

Radiation Effects and Sources, United Nations Environment Programme, 2016

Actions to Protect the Public in an Emergency Due to Severe Conditions at a Light Water Reactor, International Atomic Energy Agency, May 2013

International Atomic Energy Agency, 2015, Naturally Occurring Radioactive Material (NORM VII), Proceedings of seventh international symposium, Beijing, China, April 2013, STI/PUB/1664 (ISBN: 978–92–0–104014–5)

UNSCEAR 2006 report on Effects of Ionising Radiation

Royal College of Radiologists, Radiotherapy Dose-Fractionation, June 2006

Merck Manual for Health Care Professionals, Radiation Exposure and Contamination

Seiler, F.A. & Alvarez, J.L. 1994, The Scientific Method in Risk Assessment, Technology Journal of Franklin Inst 331A, 53-58

Office of Naval Reactors, US Navy, Occupational radiation exposure from Naval Reactors’ DOE facilities, Report NT-14-3, May 2014

Mortazavi, S.M.J. 2014, The Challenging Issue of High Background Radiation, Ionizing and Non-ionizing Radiation Protection Research Centre

Becker, Klaus, 2003, Health Effects of High Radon Environments in Central Europe: Another Test of the LNT Hypothesis?, Nonlinearity in Biology, Toxicology & Medicine, 1,1 (archived with Dose Response J)

ICRP March 21, 2011, Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant Accident

Bill Sacks, Gregory Meyerson and Jeffry A. Siegel, Epidemiology Without Biology: False Paradigms, Unfounded Assumptions, and Specious Statistics in Radiation Science (with Commentaries by Inge Schmitz-Feuerhake and Christopher Busby and a Reply by the Authors), Biological Theory, 17 June 2016

Related information

Occupational Safety in Uranium MiningNaturally-Occurring Radioactive Materials NORM