Nuclear Energy and Sustainable Development

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own. As a concept it is holistic, considering equity across countries and generations, and requiring the balancing of often-competing environmental, social and economic factors. Until about 30 years ago, sustainability from the perspective of energy supply was thought of simply in terms of the availability of fuel relative to the rate of use. Today, in the context of the framework of sustainable development – and in particular concerns about climate change and environmental degradation – the picture is more complex.

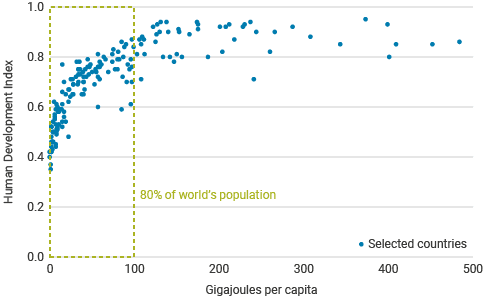

The relationship between energy consumption and human development is clear. Up to about 100 GJ per capita consumption – a level yet to be reached by 80% of the world’s population – a country can fundamentally enhance the health, educational standards, and general wellbeing of its population by consuming more energy. Any transition towards a more equitable and sustainable future must therefore be predicated on delivering the benefits of access to modern, affordable and reliable energy services to all. But doing so will increase overall energy demand: at present, the world’s poorest 4 billion people consume just 5% of the amount of energy enjoyed by those living in developed economies. For that figure to rise to 15%, global energy consumption would increase by the equivalent of an additional United States’ worth of demand.

The key question, therefore, is: how should that energy be supplied? At present, over 80% of primary energy consumption is from the burning of oil, gas and coal – unchanged since 1990. However, unregulated emissions from the combustion of fuels are causing climate change, environmental damage, and the premature death of an estimated 7 million people each year. The continued use of fossil fuels therefore has profound intra- and intergenerational social, economic and environmental implications.

The resulting dual challenge – the need to reduce harmful emissions, whilst providing more energy to more people – positions the energy sector at the heart of achieving sustainable development.

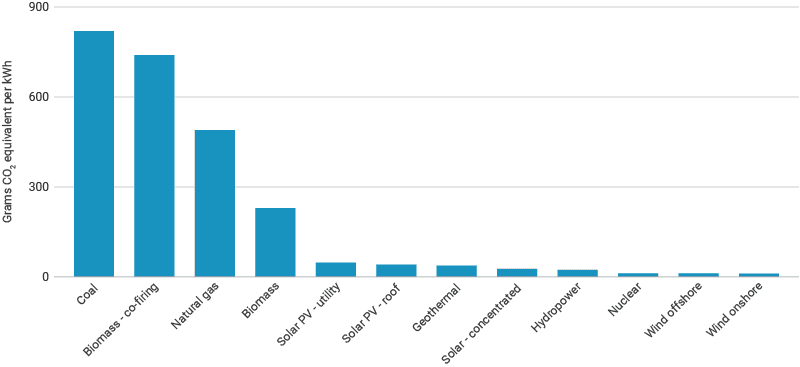

There is no technology that is fully without risk to people or the environment. For example, whilst low-carbon sources of energy do not emit carbon dioxide at the point of use, they are responsible for emissions and waste during construction, manufacturing and decommissioning. As such, any energy technology’s compatibility with sustainable development objectives must be assessed in relative terms – in the light of the alternatives.

As the only proven, scalable and reliable low-carbon source of energy, nuclear power will be required to play a pivotal role if the world is to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels to address climate change and chronic air pollution. More broadly, however, the proposition of nuclear power as a sustainable energy source is fundamentally robust due to its innate energy density, and its internalization of health and environmental costs. Using nuclear energy has numerous sustainability advantages relative to alternative forms of generation. By expanding its use, modern and affordable energy can be provided to all who currently lack access, whilst reducing the human impact on the natural environment, and ensuring that the world’s ability to meet its other sustainable development goals is not curtailed.

Defining Sustainable Development

A number of definitions have been put forward for sustainable development, but the most widely quoted is from the 1987 Brundtland Report1:

"Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”

Sustainable development is therefore the pathway to sustainability. For an activity, product or entity to be truly sustainable, it must achieve environmental, economic and social sustainability in balance: the three 'pillars'.

Figure 1: The three 'pillars' of sustainability

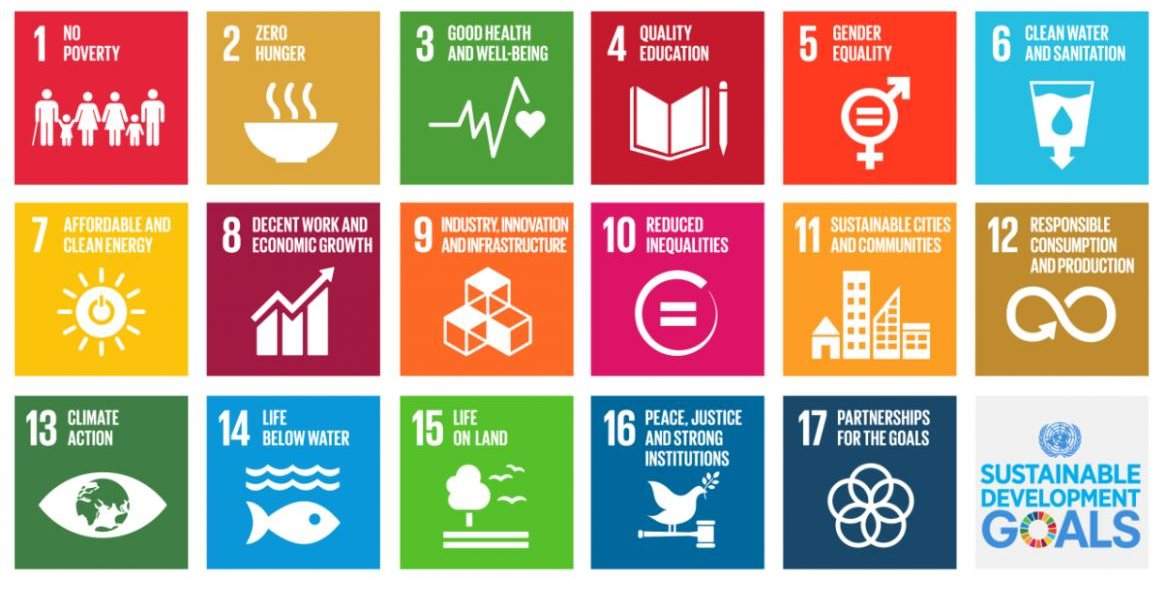

In 2015, the 193 member states of the United Nations (UN) adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development – a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity, aligned to the three pillars of sustainability. To disaggregate the bold ambitions of the 2030 Agenda, the UN agreed 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be used to guide and gauge progress.

Figure 2: The UN's Sustainable Development Goals

More energy, lower emissions

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognized that by nature, the SDGs are “integrated and indivisible”. As such, achieving progress across any of the SDGs is contingent upon progress across the others.

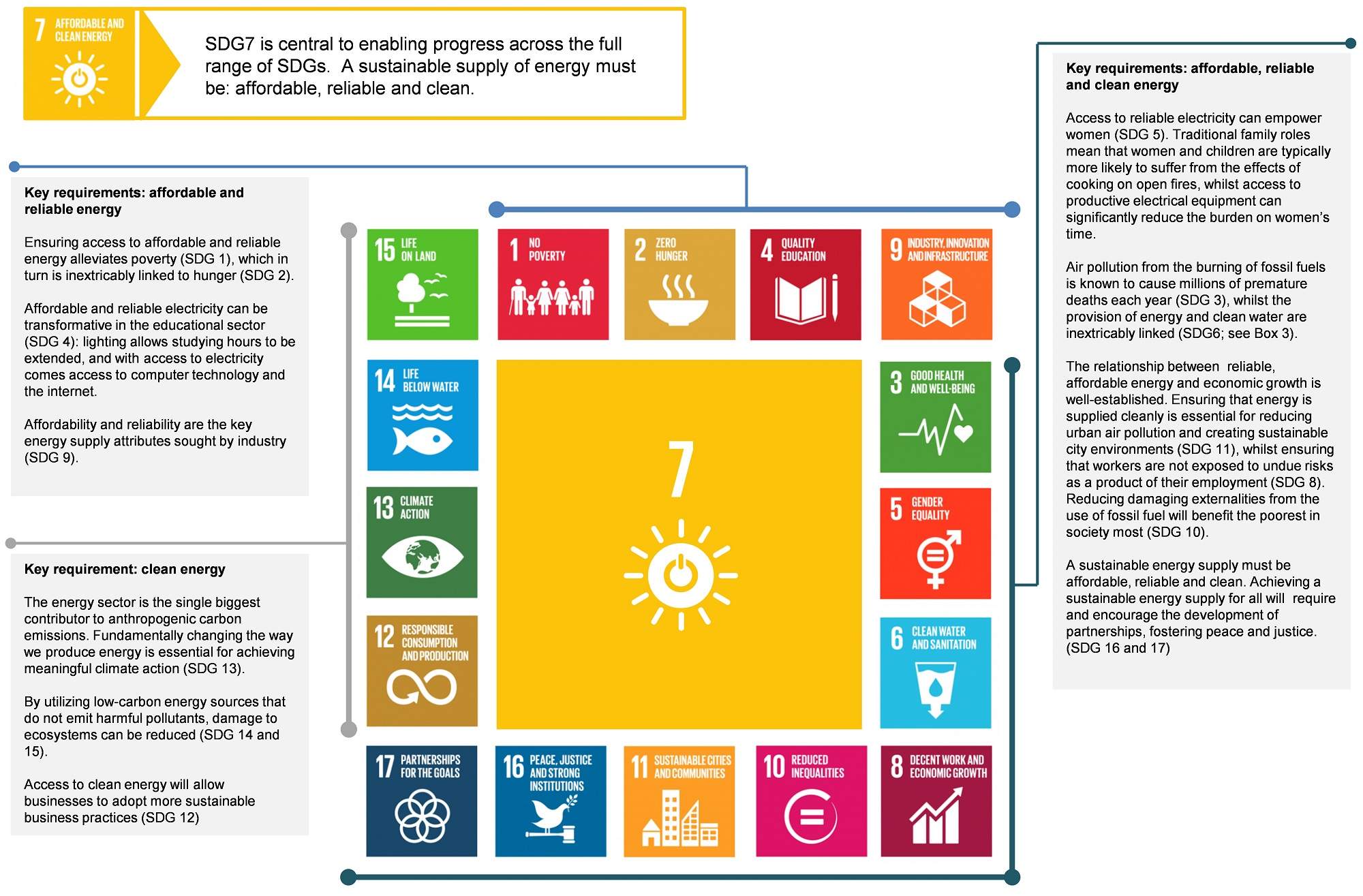

However the centrality of energy – and thus SDG 7 – is widely recognized: progress across all SDGs is contingent upon the provision of a sustainable supply of energy. Providing access to affordable, reliable and clean energy is pivotal for eradicating poverty, for improving population’s health and education, and for reducing greenhouse gases whilst continuing to support industrial development (see Figure 4).

The link between the wellbeing of a population and energy consumption is well-established for developing countries. For those countries with an annual energy consumption below 100 GJ per capita – a level that 80% of the world’s population is yet to reach2, 3 – there is a clear correlation between their energy consumption and Human Development Index (HDI)a value, which is an indicator of a nation's health, education and living standards.

Figure 3: Human Development Index and annual energy consumption per capita, 2020 (source: BP)

This relationship between human wellbeing and energy consumption explains the importance assigned to ensuring reliable access to affordable energy for all in SDG 7; reducing the share of the world’s population whose prospects are curtailed by lack of energy is essential for meeting the needs of the present. Achieving progress towards SDG 7 for the world’s growing population will require a significant increase in energy provision.

Figure 4: SDG 7 – key to all SDGs

The key question, therefore, is how best to supply those growing energy needs. Our existing energy system is built on fossil fuels, but their combustion for energy generates carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, a key contributor to climate change. The energy sector is responsible for about three-quarters of all greenhouse gas emissions, and as such, fundamentally transforming it is the single most important step towards combatting climate change.

The UN has long-recognized climate change as the defining issue of our time. Despite this explicit acknowledgement, and spectacular recent investment in renewable energy, the world burned 66% more fossil fuels for energy in absolute terms in 2021 than it did in 1990. As a result, global energy-related CO2 emissions were 63% higher.

|

Box 1: The importance of electricity At present, fossil fuels are used to meet our energy requirements for transport, residential applications (e.g. heating), and to power industrial processes. Fossil fuels are also the dominant means of generating electricity, but other sources, including hydro, nuclear, solar and wind, are used too. To transition to a sustainable energy system all energy sectors will need to be decarbonized. However, much of the focus to date has been on the electricity sector for several reasons:

Despite the focus on electricity, limited progress has been made to date. In 2021, worldwide, 133% more electricity was generated from fossil fuels than 30 years earlier. |

Can nuclear contribute to sustainable development goals?

Despite the crucial role that nuclear will need to play if the UN’s SDGs are to be achieved, there remains some opposition to the growing recognition of the energy source’s credentials for contributing towards sustainable development.

Fundamentally, nuclear energy’s competitive position from a sustainable development perspective is robust due to its energy density and internalization of health and environmental costs. Using nuclear energy brings multiple sustainability advantages over available alternatives, explaining its expanded role in almost all major studies that outline plausible pathways towards sustainable energy provision (see Box 2). An analysis of nuclear energy’s characteristics within a sustainable development framework shows that the approach adopted within the nuclear energy sector is consistent with a central goal of sustainable development of passing a range of assets to future generations while minimising environmental impacts and burdens.

|

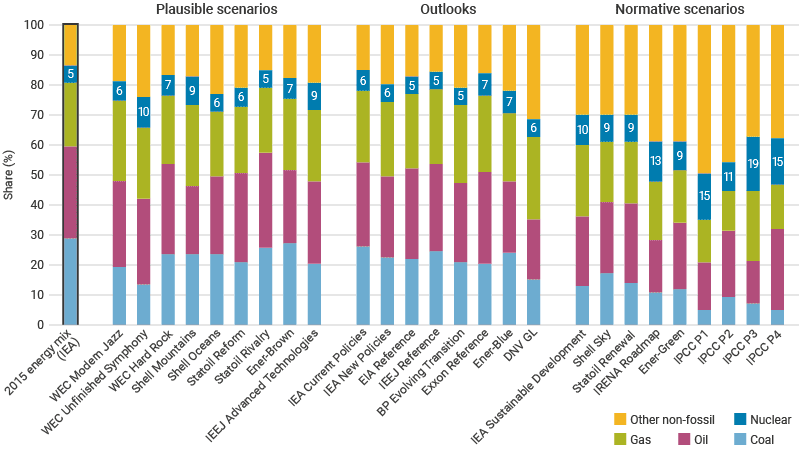

Box 2: Nuclear energy’s role in sustainable energy transitions Predicting the future of energy supply is complex, and uncertainties are high. However, it is striking that in almost all forward-looking normative scenarios, nuclear energy’s share in the mix grows substantially4. Generally, the more ambitious a scenario is in its aims for decarbonization and sustainability, the greater the role for nuclear. In the IPCC’s P3 'middle-of-the-road' scenario, for example, nuclear generation grows six-fold by 2050.

Primary energy mix by 2040 and share of nuclear energy (source: World Energy Council) |

The environmental pillar

The environmental pillar of sustainable development encompasses issues including air and water pollution, waste management, ecosystem management, and protection of natural resources, wildlife and endangered species.

Climate change

The United Nations recognizes climate change as “the most systemic threat to humankind”. As such, addressing it is generally considered the most significant and urgent sustainability challenge. Climate change is resulting from increasing concentrations of CO2 in the Earth’s atmosphere. Given that three-quarters of anthropogenic CO2 emissions result from the burning of fossil fuels for energy, the main focus should be on deploying energy technologies that emit only small amounts of CO2 per unit of energy.

On a life-cycle basis, nuclear power emits just a few grams of CO2 equivalent per kWh of electricity produced. A median value of 12g CO2 equivalent/kWh has been estimated for nuclear – similar to wind, and lower than all types of solar5.

Figure 5: Average life-cycle CO2 equivalent emissions (source: IPCC)

Ecosystem protection

The main impacts of power production on ecosystems are eutrophication (i.e. increased concentrations of chemical nutrients, primarily nitrogen and phosphorus, that damage water quality by causing oxygen depletion) and acidification (i.e. increased concentrations of acidic chemicals – caused by the absorption of atmospheric CO2 – that damage water quality, harming shellfish and coral, and leading to excessive algal growth).

Among power producing technologies, fossil fuels have by far the greatest potential to cause both acidification and eutrophication. CO2 released into the atmosphere during the combustion of fossil fuels dissolves into the oceans, increasing their acidity; and the mining, extraction, transport, waste treatment and emissions associated with fossil fuel use contribute to their high eutrophication potential. By contrast, both the acidification and eutrophication potential of nuclear power are estimated to be among the lowest of all available generation technologies6.

Figure 6: Lifecycle eutrophying emissions for 2020, in grams of phosphorus equivalent per MWh (source: Carbon Neutrality in the UNECE Region: Integrated Life-cycle Assessment of Electricity Sources, UNECE (March 2022)

Land and water use

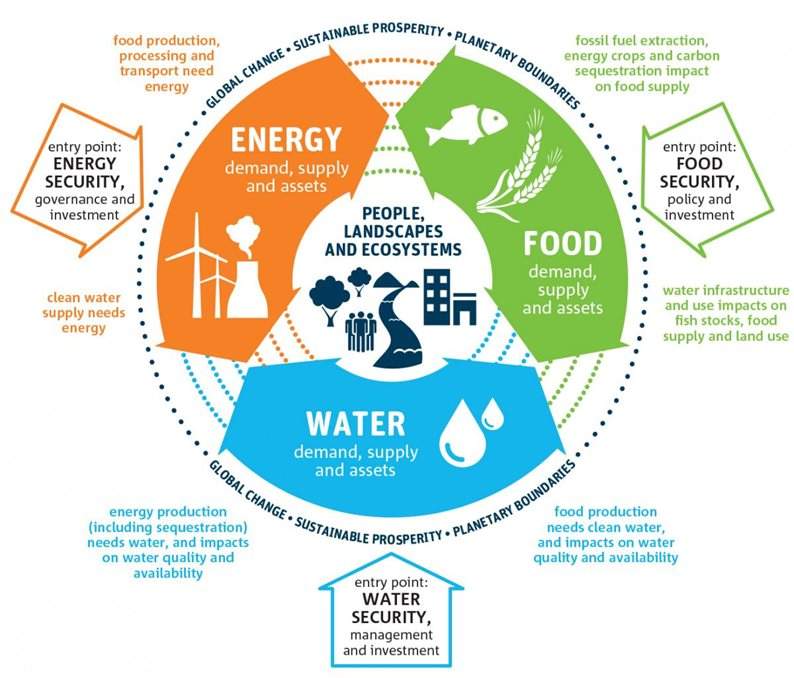

Land and water usage are key criteria for assessing the sustainability of different power production technologies. The power sector competes for limited resources with other important sectors such as agriculture, industry and housing, and the emergence of a new concept known as the water-food-energy nexus reflects the growing appreciation of the interconnectedness of policy decisions in these three areas.

Nuclear power plants produce huge amounts of low-carbon power and require less land to do so than any other energy source. The UN expects two-thirds of people to be living in urban areas by 2050 – an additional 2.5 billion individuals – where land is at a premium. Coupled with the need to preserve land to prevent loss of biodiversity, it is likely that nuclear energy’s unique land-use advantages will prove increasingly determinative in the future.

|

Box 3: The water-food-energy nexus Demand for water, food and energy is increasing, driven by rising global population and prosperity, as well as urbanization, dietary changes and economic growth. More than one-quarter of the world’s energy is used for the production of food, and the agricultural sector is the largest single consumer of freshwater resources. The inextricable link between achieving water, energy and food security has driven recognition that policy decisions on each cannot be made effectively in isolation. The nexus approach is designed to integrate management across the three closely-related sectors.

The water-food-energy nexus (source: International Water Association) |

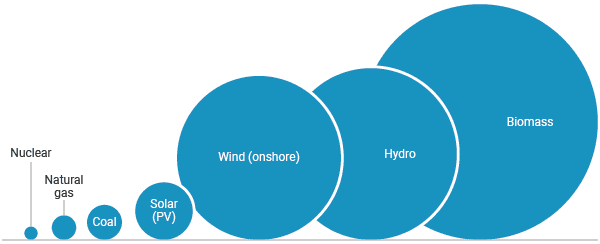

A large two-unit nuclear power plant can provide electricity for 4-5 million people from a generating footprint of just 2 square kilometres. However, the land use of all energy-generating technologies extends beyond their generating footprint, and includes the required mining of raw materials and, for conventional sources of power, their fuel cycle. Taking this into account, the land use of biomass, hydro, wind and solar are between one and three orders of magnitude greater than nuclear7.

Figure 7: Relative land use (fuel mining and generating footprint) of electricity generation options per unit of electricity (source: Brook & Bradshaw, 2015)

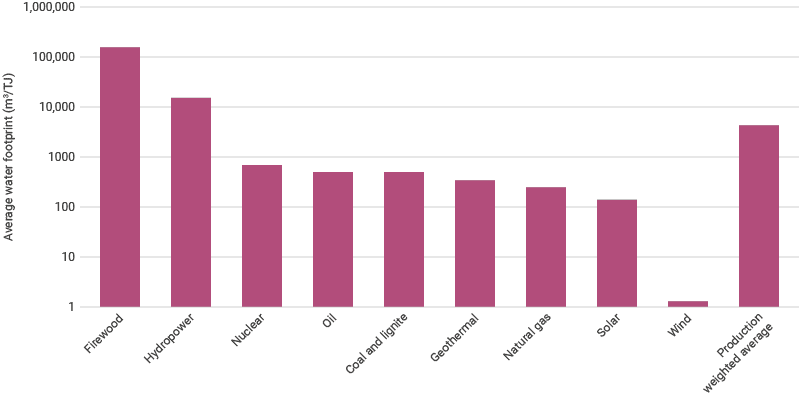

At some stage during supply, construction or operation, all electricity generating options consume water. Wind and solar energy have the smallest water 'footprints', whereas biomass and hydropower have the largest. Fossil fuels and nuclear consume significant quantities of water in the operational phase for cooling8.

Fresh water is a valuable resource in most parts of the world. Apart from proximity to main load centres, there is no reason to site nuclear power plants away from a coast, where they can use once-through seawater cooling. The high energy density of uranium means that logistical requirements for fuel are modest (about 200 tonnes for a large reactor annually versus over 3,000,000 tonnes for an equivalent coal plant) allowing for flexible siting of nuclear power plants. In the event that water is so limited that it cannot be used for cooling, and a coastal location is not available, plants can be sited away from the load demand, but this will incur additional transmission costs.

Whilst nuclear power plants require significant quantities of water for cooling, their ability to provide large amounts of power is increasingly being used to secure water supplies in areas of scarcity. Where potable water cannot be obtained from streams and aquifers, desalination of seawater, mineralized groundwater or urban waste water is required. Most desalination at present is powered by fossil fuels, but nuclear desalination has been used for many years in countries such as Japan, India and Kazakhstan.

Figure 8: Water consumption per unit of electricity and heat produced 2008-2012 (source: Mekonnen et al., 2015)

Waste

The careful management of waste streams is a key sustainability consideration in order to prevent short- or long-term harm to humans and the environment. All energy-producing technologies create waste, but the amount produced, the risk it poses, and the means of management vary widely.

The energy density of fuel used for electricity generation is one key determinant of the magnitude and manageability of waste streams. Uranium’s exceptionally high energy density means a relatively small amount of fuel is required per unit of energy produced. Using less fuel reduces the scale of fuel extraction activities and transport requirements – in turn reducing the chance of unintended environmental releases – and results in the creation of less waste. Contrary to popular belief, therefore, one of the benefits of producing electricity from nuclear energy is that its waste streams are small, and therefore innately manageable. It is for this reason that nuclear energy is the only form of electricity generation to fully contain its emissions, effluents and waste.

Unlike nuclear energy, some energy sources dispose of wastes to the environment, or have health effects which are not costed into the product. These implicit subsidies, or external costs as they are generally called, are nevertheless real and usually quantifiable, and are borne by society at large. Their quantification is necessary to enable rational choices between energy sources. Nuclear energy provides for waste management, disposal and decommissioning costs in the actual cost of electricity (i.e. it has internalized them), so that external costs are minimized.

The social pillar

Human health – air pollution

Air pollution arising from the use of carbon-based fuels for energy is one of the biggest threats to human welfare. The World Health Organization estimates that about 7 million people die prematurely each year as a result of air pollution exposure.

Nuclear power plants emit virtually no air pollutants during operation, and because they are reliable and can be deployed on a large scale, they can directly replace fossil fuel plant. NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Columbia University’s Earth Institute estimated that the use of nuclear power prevented over 1.8 million air pollution-related deaths between 1971 and 2009.

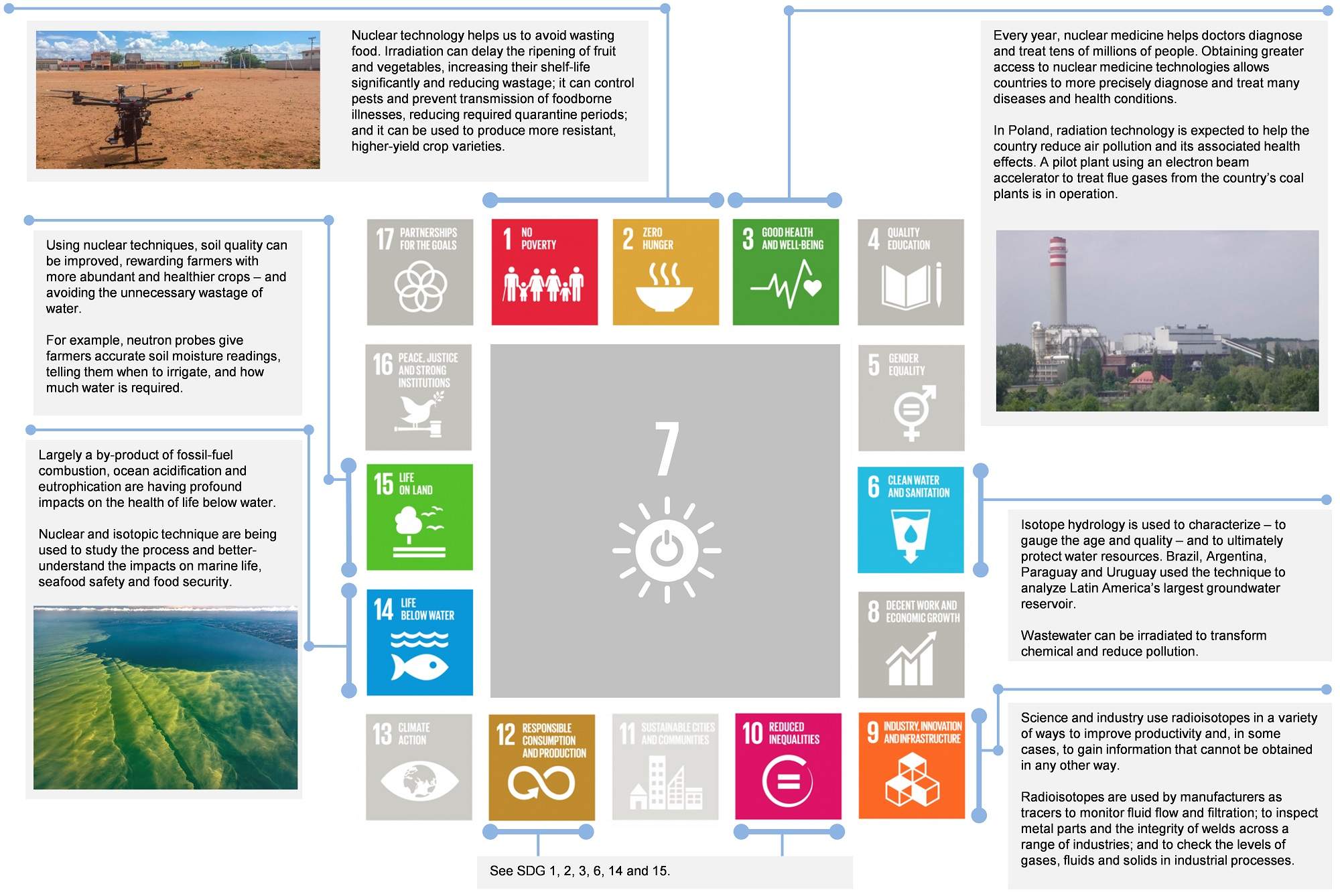

There are numerous non-power uses of nuclear technology that contribute to fulfilment of human 'needs'. For example: the provision of nuclear medicine; helping to control the spread of infectious diseases; and securing reliable supplies of clean water, sanitation and food (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Examples of the contribution of non-power nuclear technologies to the SDGs

Human health – radiation

Radiation is a well-understood process, with natural sources accounting for most of the radiation people receive each year. Doses received average 2.4 mSv/yr, but vary widely by location, driven by factors such as underlying geology and altitude. The highest known level of background radiation affecting a substantial population is in the states of Kerala and Madras in India where some 140,000 people receive doses which average over 15 mSv/yr from gamma radiation, in addition to a similar dose from radon. Comparable levels occur in Brazil and Sudan, with average exposures up to about 40 mSv/yr to many people. Lifetime doses from natural radiation range up to several thousand millisieverts. However, there is no evidence of increased cancers or other health problems arising from these high natural levels.

20 mSv/yr is the current average allowed limit for nuclear industry employees and uranium miners during normal operation. The millions of nuclear workers that have been monitored closely for 50 years have no higher cancer mortality than the general population but have had up to ten times the average dose.

Nuclear power is the only technology that systematically measures and accounts for radioactive emissions. However, exposure to above-background radiation is not exclusive to nuclear power-related activities. UNSCEAR has estimated that both occupational and public exposures from electricity generation are higher for workers in the coal industry, for example.

Employment

Nuclear power plants can operate for over 60 years, creating long-lasting, high-paying jobs for people from a range of fields and educational backgrounds. Undertaking a nuclear power programme therefore represents a long-term investment in human capital.

Investment in capital-intensive projects tends to spill over into other industries and economic sectors. A modern gigawatt-scale nuclear power plant employs 500-1000 workers directly. But throughout both its construction and operation, it requires a complex supporting supply chain (e.g. construction, manufacturing and consultancy services), creating attractive indirect and induced employment opportunities.

During construction of a large, modern plant, thousands of workers may be onsite. At Hinkley Point C (pictured), over 8000 workers will be onsite during the peak of construction.

A study of the European nuclear industry by Deloitte suggested that nuclear provides more jobs per TWh of electricity generated than any other clean energy source. According to the report, the nuclear industry sustains more than 1.1 million jobs in the European Union. In addition, each gigawatt of installed nuclear capacity generates €9.3 billion in annual investments in nuclear and related economic sectors, and provides permanent and local employment to nearly 10,000 people. For every €1 invested, the nuclear industry generates an indirect contribution of €4 in GDP, and every direct job creates 3.2 jobs in the EU as a whole.

The economic pillar

Resource adequacy, preservation & opportunity cost

Uranium has no significant use other than nuclear energy production. Producing electricity with uranium extends the overall resource base available for human use, provides greater diversity of choice and allows the use of other resources, such as hydrocarbons, where they are most effective e.g. for transportation or petrochemicals.

Uranium is plentiful and is distributed among a wide range of geopolitically diverse countries. The distribution of uranium reduces the risk of market disruptions of the nature experienced during historical oil and gas crises.

Resource efficiency and material throughput

The focus on power supply options defined as 'renewable' over the past several decades reflects the importance attached to the preservation of finite resources. Renewable sources of energy are those generated from natural processes that are continuously replenished. Renewable technologies, therefore, are defined as those that are not fuelled by a finite resource.

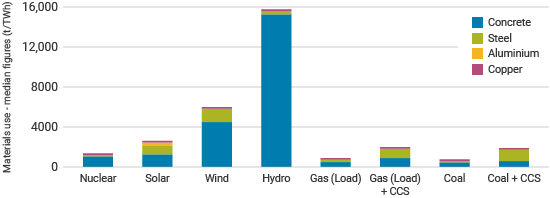

Intergenerational equity is a key principle of sustainable development, and so the purported advantage of renewable energy options – that they do not diminish finite fuel resources for future generations – is valuable. However, fuel supply is just one aspect of the material requirements for power generation. All means of generating electricity require infrastructure that consumes finite resources, with the major material inputs by volume outside of fuel supply typically concrete and metals (e.g. aluminium, cooper, steel). Estimates for the use of key bulk materials and copper per TWh for different technologies have been produced by former environmental organization Bright New World9, based on a literature review of studies on this topic.

| Nuclear PWR | Solar | Wind | Hydro | Gas (load following) | Gas (load following) + CCS | Coal | Coal + CCS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete | 1060 | 1220 | 4470 | 15,320 | 390 | 820 | 450 |

520 |

| Steel | 130 | 940 | 1450 | 330 | 320 | 970 | 160 | 1170 |

| Aluminium | 0.3 | 287.5 | 17.4 | 8.7 | 5.7 | 21.4 | 1.6 | 37.4 |

| Copper | 2.5 | 68.0 | 39.1 | 4.8 | 5.4 | 8.8 | 3.0 | 11.8 |

| Capacity f. | 85% | 28% | 35% | 50% | 30% | 30% | 85% | 85% |

| Lifespan | 60 | 30 | 30 | 100 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Table 1 and Figure 10: Major materials for different generating technologies, tonnes per TWh (source: Bright New World)

The aim of reducing material inputs is a central concept of sustainable development. Using material in the production, transport and implementation of power producing technologies will consume energy in the form of fossil fuels, and as such the metric of material throughput is important in consideration of energy efficiency as well as life-cycle carbon emissions. But more broadly, resource efficiency is a key aim in itself. Consumption of primary materials is expected to more than double by 2050. Using nuclear energy to generate electricity is one means by which resource demand can be reduced to more sustainable levels.

Affordability

Affordability is a key component of SDG 7. The benefits of access to modern energy are profound, but the aspiration of ensuring access for all can only be realized if it is affordable.

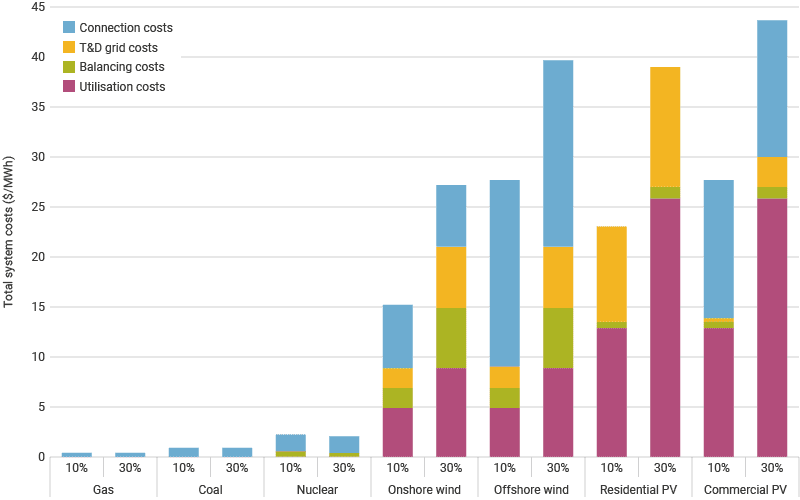

The relative affordability of electricity supply options is a function of generation costs as well as the costs they impose on the system as a whole. Generation costs are typically reported using the levelized cost of electricity generation (LCOE) metric, which is a measure of the ratio of the total costs of a generic plant (capital and operating), to the total amount of electricity expected to be generated over that plant’s lifetime. LCOE as a metric is relatively simple and transparent, and so is widely referenced. However, its ability to assess overall costs to society are limited. In deregulated markets, revenues are uncertain over a generator’s lifetime making the metric less pertinent; and the metric does not attempt to capture the markedly different system costs of technologies.

System costs have always existed, but the growth in variable renewable energy sources has promoted the topic in recent years. System costs include required outlays for distribution and transmission, and most importantly, backup for the inherent variability of some renewable energy. System costs are difficult to assess, as they depend on the characteristics of the system in question, the time frame considered, location and numerous other factors. Whilst there is uncertainty, estimates are consistent in that system costs for variable energy sources are significant, increase non-linearly with growing shares of electricity generation, and are an order of magnitude higher than for dispatchable technologies10.

The costs of the system as a whole are ultimately borne by society, and so, given the increasing use of variable renewable energy, it is important that system costs are internalized to ensure that policy decisions can be properly directed towards maximizing affordability.

Negative effects beyond the system itself (i.e. negative externalities) related to the provision of electricity are increasingly being recognized as significant and complicate the picture further. Negative externalities related to electricity generation – most notably the emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants – represent a social cost that may impact the true affordability of different electricity supply options. It is well documented that the social and economic costs of climate change and air pollution are significant. In order to better-understand the socially optimal level of externalities (relative to production) it is imperative that the relative costs of different supply options include a reasonable estimate of their impacts on emissions and the climate.

Nuclear energy is cost-competitive based on a simple LCOE comparison, particularly at low discount rates. Its unique attributes of providing predictable, reliable supply that is low-carbon means that inclusion of system costs and negative externalities both markedly improve the relative affordability of nuclear energy.

Figure 11: Grid-level system costs for dispatchable and renewable technologies (source: OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, 2018)

Notes & references

Notes

a. The Human Development Index (HDI) is a United Nations Development Programme statistical tool to measure a country's level of social and economic development. The social and economic dimensions of a country are based on the health of its people, their level of education attainment and their standard of living. A country scores a higher HDI when the lifespan of its people is longer, the education level is higher, and the gross national income per capita is higher. [Back]

References

1. United Nations, Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future ('Brundtland Report') (1987) [Back]

2. United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Reports [Back]

3. BP Energy Outlook: 2019 edition [Back]

4. World Energy Council, World Energy Scenarios 2019, The Future of Nuclear: Diverse Harmonies in the Energy Transition (2019) [Back]

5. Steffen Schlömer (ed.), Technology-specific Cost and Performance Parameters, Annex III of Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2014) [Back]

6. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Carbon Neutrality in the UNECE Region: Integrated Life-cycle Assessment of Electricity Sources (March 2022) [Back]

7. Barry W. Brook and Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Key role for nuclear energy in global biodiversity conservation, Conservation Biology, 29, 3 (2015) [Back]

8. Mesfin Mekonnen et al., The consumptive water footprint of electricity and heat: a global assessment, Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology (March 2015) [Back]

9. Bright New World, Materials use in a clean energy future (June 2021) [Back]

10. OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, The Full Costs of Electricity Provision (2018) [Back]

Appendices

Nuclear Energy and Sustainable FinanceRelated information

Nuclear Power in the World TodayEconomics of Nuclear Power

Radioisotopes in Medicine

The Many Uses of Nuclear Technology

Nuclear Power and Energy Security